Huizhou merchants, also known as Huishang (徽商), were one of the most influential merchant groups in Chinese history. Their rise and success were largely shaped by the unique geography and socio-economic conditions of the Huizhou region. Situated in a remote, mountainous area with limited arable land, Huizhou faced challenges that forced many of its residents to seek livelihoods beyond agriculture. Over time, a culture of commerce developed, and Huizhou merchants became renowned for their business acumen, cultural sophistication, and adherence to Confucian principles.

The Origins of Huizhou Merchants

Before the Han dynasty, the population of Huizhou was sparse due to the region’s rugged terrain and dense forests. However, following the waves of migration from northern China during periods of political upheaval, the population grew significantly. As the number of people increased, the limited arable land became insufficient to support the local population. Faced with these harsh conditions, many Huizhou people turned to commerce as a means of survival.

Initially, Huizhou merchants engaged in the trade of local products such as timber, tea, and grain. The region’s rich natural resources played a crucial role in fostering the early growth of commerce. Timber, for instance, was widely used for construction, ink-making, oil production, and papermaking, all of which provided significant trade opportunities. Additionally, the area’s reputation for producing fine teas, such as Huangshan Maofeng and Keemun black tea, further contributed to the prosperity of Huizhou merchants.

The Golden Age of Huizhou Merchants

The golden age of Huizhou merchants spanned from the mid-Ming dynasty (1368–1644) to the end of the Qianlong Emperor’s reign in the Qing dynasty (1736–1796). During this period, Huizhou merchants dominated China’s commercial landscape. Their wealth, influence, and extensive business networks stretched across the empire, and they held a prominent position among merchant groups. By this time, commerce had become the primary occupation for Huizhou men, with approximately 70% of adult males engaged in trade.

Huizhou merchants not only prospered within China but also expanded their trade to international markets. Their trading routes extended to Japan, Southeast Asia, and even as far as Portugal, showcasing their global reach. The success of Huizhou merchants during this era made them a vital part of China’s economic system, with their activities ranging from the sale of salt, tea, and timber to the production and trade of paper, ink, and silk.

The Decline of Huizhou Merchants

The decline of Huizhou merchants began in the late Qing dynasty, as the feudal system weakened and the burdens of heavy taxation and corruption increased. In 1831, a government reform led by Tao Zhu, the governor of the Liangjiang region, dismantled the Huizhou monopoly on the salt trade, marking the beginning of their downfall. Additionally, the Opium Wars (1839–1860) and the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864) further destabilized Huizhou merchants, leading to significant financial losses.

The influx of foreign goods and capital following China’s defeat in the Opium Wars dealt a severe blow to Huizhou merchants, whose traditional industries were outcompeted by foreign imports. Many Huizhou traders struggled to adapt to the changing economic landscape, and their influence gradually waned.

Confucian Values and the Huizhou Merchants

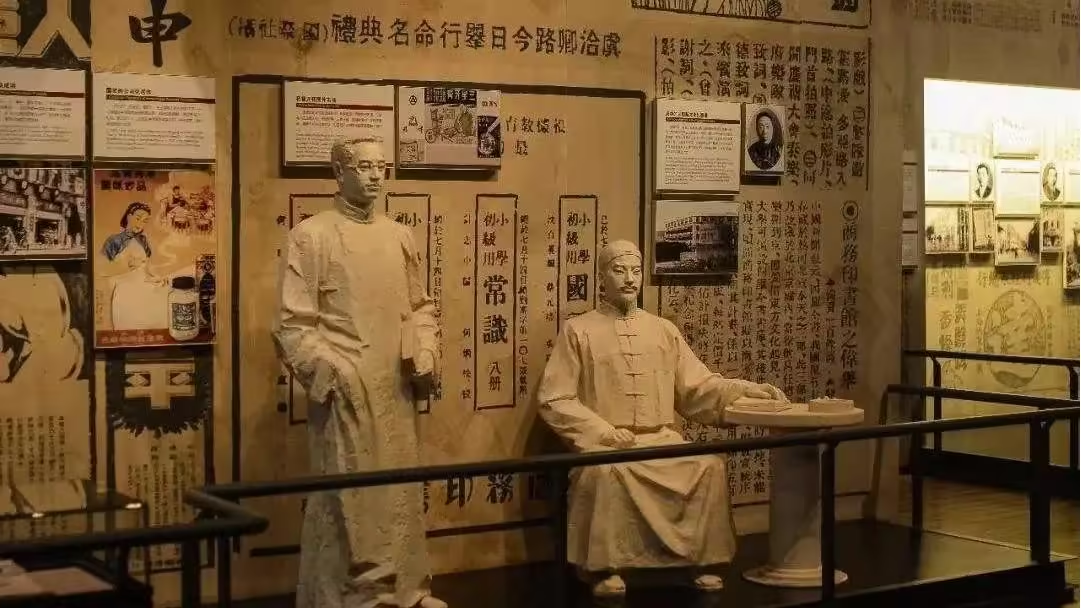

One of the defining characteristics of Huizhou merchants was their deep connection to Confucian values. Known as “scholar-merchants,” they combined commercial pursuits with Confucian ethics, which emphasized integrity, loyalty, and the importance of education. Many Huizhou merchants invested in education and cultural pursuits, with some becoming patrons of the arts and scholars themselves.

Prominent Huizhou merchants, such as Hu Xueyan, Wang Yinggeng, Jiang Chun, and Hu Kaiwen, exemplified this dual identity of being both businessmen and scholars. Their ability to balance commerce with Confucian ideals helped shape their reputation as ethical and cultured merchants, setting them apart from other trading groups.